In a world of iPads, online bookselling behemoths and eReaders, Robert Fedele finds there’s still a place for independent bookshops where printed books are customers’ friends.

DEB Force is remarkably upbeat for someone in her predicament.

Happy and at ease, she is someone who by her own admission loathes change, and tries to avoid it as long as possible.

We’ve been chatting for barely a minute before Force, who owns the Sun Bookshop in Yarraville, breaks to serve a customer.

‘‘It’s supposed to be fantastic, this book,’’ she enthuses as she wraps the chosen item.

The middle-aged man returns the smile, says it’s for a mate’s 40th, then acknowledges the elephant in the room.

‘‘Are you surviving . in the online world?’’ he asks sheepishly.

Force replies: ‘‘All of the independents, everyone I know, has said business is so much better now,’’ referring to last year’s collapse of Redgroup Retail and the resulting closure of 96 Borders and Angus & Robertson stores across the country.

Anecdotally at least, independent bookshops are reporting healthy sales during a delicate period of rapid digital change, where many people consider it inevitable that books will be replaced by devices such as iPads and eReaders.

In Melbourne’s west, where bookshops can be counted on one hand, local stores are proving surprisingly resilient.

Force has loved books since she was a child, when she would visit her grandmother, who had a huge collection stored in her garage, grab a book and read it from cover to cover.

She moved to Yarraville 25 years ago and opened the bookshop with a friend in 1998.

‘‘Neither of us had ever been booksellers. We just jumped in and did it without analysing it or thinking about it.

‘‘And at first we were saying, ‘It’s gonna be great, we’re not gonna have any customers and we’ll be able to read books all day’. And after about a week we went, ‘Ohhhhhhh, no, we need customers’.’’

That happy-go-lucky nature hasn’t deserted Force, who even today prefers to take things at a snail’s pace.

Fourteen years ago she knew nothing of the internet and tried to send an email though she didn’t have an account.

Today she is grappling with having the capability to sell eBooks and finding suppliers.

The biggest threat is perhaps UK-based online store The Book Depository, which offers six million dirt-cheap books with free delivery worldwide.

Does developing technology worry her?

‘‘It worries me that I can’t keep up with it,’’ Force laughs.

‘‘At the same time I think there’s still a place for my shop even without having that ability. And I think it will change and I need to do something about it pretty soon.’’

‘‘I like to imagine that sometimes people want the online world and sometimes they don’t.’’

Force’s popular bookshop is attached to Yarraville’s famed Sun Theatre.

‘‘Without the cinema I probably wouldn’t have survived. It gives people a reason to come to Yarraville.’’

Bookseller Paul O’Brien is resigned to the fact that change is unavoidable.

The 72-year-old opened the Niddrie Arcade Book Exchange & Stamp Shop in 1981 after retiring from the textiles industry.

He’s an avid stamp collector, and it was his wife, who he describes as a manic reader, who steered him towards selling secondhand books.

‘‘Only secondhand,’’ he says matter of factly. ‘‘I’ve never sold a new book. And it’s a book exchange. You can buy a book or you can swap a book, any book, for a similar book for $2.’’

O’Brien built up his tiny shop from scratch, starting with a few planks of wood which became shelves, and a handful of books.

Today it’s crammed with books as far as the eye can see, narrow aisles with 65,000 or thereabouts.

In the early ’90s he started selling schoolbooks and created a niche. Today they account for 80 per cent of his trade.

O’Brien bites the frame of his glasses while gathering his thoughts about the future of printed books.

‘‘I think it’s the end of schoolbooks. Already there are some schools that have no paper. A child has a laptop. The next rung down below that is, ‘Oh you can buy a book, which is a piece of plastic which allows you to get on to a computer’.’’

O’Brien isn’t laying down and plans to beef up the book exchange.

He doesn’t subscribe to the theory that there’s been a decline in readership and believes there are enough books out there already to satisfy everybody.

‘‘People who are 35 or 40 or more won’t have a bar of it,’’ he says about the online world.

‘‘And the books that people read, generally, are of the last 25 or 30 years.’’

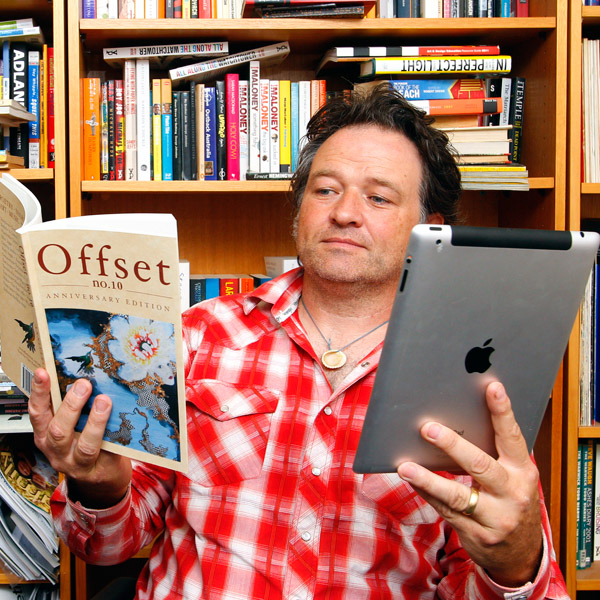

John Weldon, a lecturer in professional and creative writing at Victoria University, has closely watched the debate unfold, referring to the introduction of Kindles in 2007 and the iPad in 2010 as catalysts behind the idea of the literary novel becoming an endangered species.

‘‘That was the real moment when all of a sudden people thought, ‘I’ve got a piece of technology here almost as portable as a book and as convenient as a book’,’’ he says.

Engaging and amiable, Weldon speaks with gusto of his love for the printed book, but likewise trumpets the convenience of the iPad.

He agrees there has been a shift towards new technologies but isn’t sure it means the end of books, using the analogy that television didn’t kill film.

‘‘Everyone thought when video recorders came out in the early ’80s, ‘Well, that’s it. No one’s going to ever go to the movies again’. What tends to happen is a new medium comes along and it pushes the other ones aside, reduces their market share a little bit and finds a place for itself.

‘‘It may end up taking over everything and we may end up with a purely digital media world. Or we might find that it establishes a presence for itself but we still have printed books, but maybe less of them.’’

Weldon, who is completing a PhD on the move from print to digital books, considers the online world a blank canvas and says it opens new possibilities for authors and readers.

He doesn’t believe it will replace the traditional book. It just might offer an alternative.

Asked about the future of bookshops, Weldon says new and existing stores need to become smarter about attracting an audience.

‘‘It would be a very brave person to open up a bookshop now. But if you do open up one now you’ve got to be smart about it. You can’t just get a truckload of shelves and whack a bunch of books on them. A bookshop needs to be a destination.’’

In seaside Williamstown, Sue Martin has been running Book and Paper for three years with co-owner Wenche Osland.

They hold frequent events with authors and have organised book clubs.

‘‘That’s to encourage people to see us as an alternative to other possibilities,’’ Martin says.

‘‘We are a business. We love what we do and we’re passionate about that but it’s about growing the business. It’s about looking beyond just selling.’’

Martin taught high school English for 20 years and ventured into books when the classroom lost its appeal.

An avid, lifelong reader, she doesn’t entertain the notion that the printed book is dead.

She believes there’s a place for eBooks, but that they will never replace what she refers to as ‘‘real books’’.

One of her longest customers, Melba Mahoney, describes a book as ‘‘like having a friend’’.

‘‘People want to touch, want to hold. It’s something tangible. I think people are drawn to that,’’ Martin says.

‘‘Our lives are so full of devices now. Everything’s electronic. But a real book offers an alternative to that.’’

Book and Paper’s business, like most independents, is healthy, and has improved since the demise of the bigger fish.

Martin concedes there’s undeniable pressure on bookshops, which is precisely why she believes her store will survive the online onslaught.

‘‘That’s always what we wanted to be, a community store,’’ she says when asked if her little hub had brought people together. ‘‘And to know our customers and have that relationship with them.

‘‘I think there’s a difference between general retail and a bookstore because people connect with books in a different way. People are drawn to a bookstore because it’s about something more. There’s soul in books.’’