SEE VIDEO BELOW

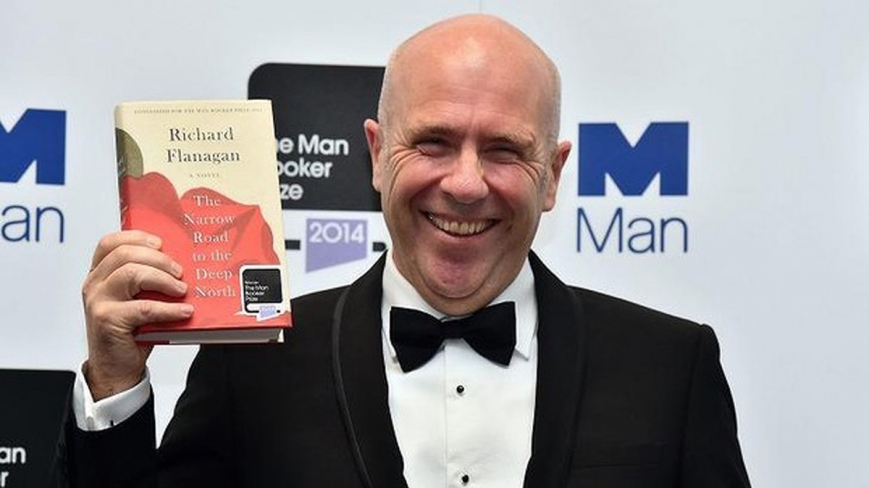

Tasmanian author Richard Flanagan has won one of the world’s most prestigious literary prizes, the 2014 Man Booker, for his masterpiece of love and death, The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

Chair of the judging panel AC Grayling praised the book, about Australian soldiers on the Burma Railway – and what came after – said the book was “profound and often harrowing”.

He said the best novels on the award’s shortlist had left the judges unable to pick up another book straight after finishing them, but instead “relishing the aftertaste”.

“I feel as if I have been to the moon and back on a comet’s tail,” Prof Grayling said.

On accepting the award Flanagan joked that the Booker was sometimes seen in Australia as a chook raffle, “but I just didn’t expect to be the chicken”.

“I’m astonished,” he said of the win. “You do not expect these strokes of good fortune to come your way, you’re just grateful to be back at the table the next day writing.”

He came from a tiny mining town in a rainforest and his grandparents were illiterate, he told the prestigious gathering of literary greats in London’s Guildhall.

“Novels are life, or they are nothing,” he said, thanking his wife (who was there to see him accept the prize) for accompanying him on the writer’s “journey into humility”.

“(To be a writer) it’s to be defeated by ever greater things,” he said, saying his wife had “travelled with me over many dark times with love, with grace, with dignity”.

He also thanked his Australian publisher for her “rare genius” in helping him and other Australian writers “out of the literary ghetto”.

In a possible breach of royal protocol, Flanagan hugged the prize’s presenter – the Duchess of Cornwall – when he came up on stage to accept the award.

“She is such a sweet woman and she is very nice and I didn’t think to respond in any other way,” he explained afterwards.

Flanagan said he did not think literature was about borders – the miracle was that in every year, in all sorts of places, good books continue to be written, he said.

Flanagan’s father, a survivor of the Burma Death Railway, died the day he finished the book.

“It was the book I had to write in order to continue to keep writing,” Flanagan said.

Sipping a champagne after winning the prize, Flanagan said the £50,000 award “in essence means I can continue to write”.

Two years ago he had been considering going to work on the mines because he had spent so long on this book.

He hopes to get the next one out much more quickly – possibly even next year, though winning the Booker may change his schedule.

Flanagan also said he didn’t share general pessimism about the death of the novel.

“Much has been made about the death of the novel and the end of literature,” he said. “I don’t share that pessimism because I think it is one of the great inventions of the human spirit.

“It allows an individual to speak their truth unfettered by the dictates of either power or money… it continues to be heard across the continents and through the decades.”

He looked forward to going back to Tasmania, “pulling down the shutters and continuing writing” he said.

Prof Grayling said that in some years “very good books” won the Man Booker Prize – but this year “a masterpiece” had won it.

“It felt like being kicked in the stomach by several donkeys, all at once,” said Prof Grayling about reading the book. “It really is an extremely powerful book.”

“It has a real seam of truth in it which constantly makes you catch your breath. It’s going to live in the canon of world literature.

“War and love, sex and death, the eternal braid of occupations… It’s a deeply felt book. It has these extra dimensions to it. It does stand out from what was a fantastically strong year. All fiction in English published this year – a lot of strong competition there.”

But the ‘crowdsourced’ response of the judges had been that “we were in the presence of a piece of work that really has ‘it’, whatever ‘it’ is,” Prof Grayling said.

This was the first year that the previously Commonwealth-only prize has been open to all English language writers.

This story first appeared in The Age