The neurosurgeon who narrowly survived a stabbing attack in the foyer of Western Hospital has warned that further attacks will occur unless new measures to protect staff and patients are introduced.

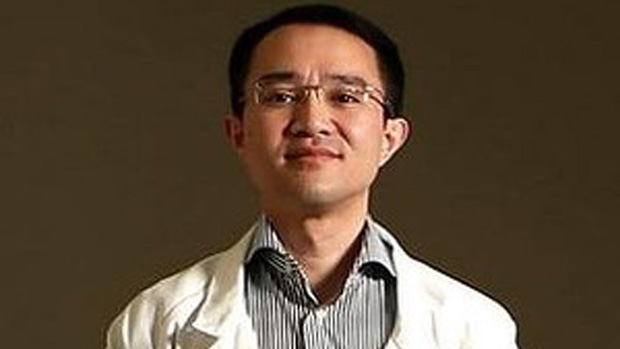

Michael Wong was stabbed 14 times in his arms, chest, abdomen and forehead as he arrived for work on February 28 this year, before being dragged to safety by passers-by.

He said he was unaware of any major changes made in Victorian hospitals since the attack, which had highlighted security failings.

Mr Wong said secure entrances for hospital staff, restricted access to wards and regular security patrols of public areas were some of the measures needed to prevent repeat attacks.

Western Health chief executive Alex Cockram told ABC radio last month that the attack on Mr Wong was “an extraordinarily tragic event, out of any comprehension and understanding”.

“It’s difficult to see how any level of security changes would make a difference, except to have everyone searched like an airport coming through the front door, which is very difficult in a hospital environment,” she said.

But Mr Wong said the suggestion that no security measure could have prevented him being attacked was “a bit like saying, ‘Do whatever you want, we surrender’ “.

“There has to be improvement,” he said. “The next doctor who gets stabbed is not going to be as lucky as me. The next doctor will be dead with a widow and kids, who will never see their father again.”

Mr Wong’s call for action ahead of November’s state election is echoed by doctors and nurses who say violence is a major and growing problem in Victoria’s public hospitals.

They say violence from patients and relatives is being fuelled by overcrowding in emergency departments, inadequate mental health beds and increasing use of methamphetamines such as ice.

Data released to Fairfax Media under freedom of information laws revealed that violent patients armed with knives, chairs and syringes threatened or attacked staff in more than 100 “code black” incidents at 11 Melbourne hospitals in 2012-13.

That came on top of almost 14,000 other incidents of aggressive or threatening behaviour prompting “code grey” security calls at 14 hospitals over the same period. Incidents included staff being spat at, bitten, kicked and punched.

Reported data is just the tip of the iceberg, with many incidents not being reported due to inadequate follow-up and a culture of accepting safety risks.

Only a fraction of assaults are reported to police. Victorian chairman of the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine Simon Judkins said doctors could be reluctant to do so because they feared retribution from disgruntled people who knew where to find them.

“It’s not like a random assault in the street – this is happening at your work,” he said. “You are worried you might leave at 11 o’clock one night and walk across the carpark and something will happen.”

The Australian Medical Association said healthcare workers were being forced to accept violence as part of their daily work, with the government slow to respond to the recommendations of a 2011 parliamentary inquiry into violence in Victorian hospitals.

The inquiry was established following widespread opposition to the government’s promise during the 2010 election campaign to install armed, protective services officers (PSOs) in emergency departments.

Australian Nursing Federation state assistant secretary Paul Gilbert said the promise had acknowledged that hospital violence was a major problem, but little had been achieved from the resulting inquiry and even after the high-profile attack on Mr Wong.

He said there were still hospitals in Victoria that did not have a “code grey” system for responding to aggression and violence, almost a decade after a ministerial taskforce recommended the government establish a standard response for hospitals across the state.

Mr Gilbert said staff working in hospitals without a code grey system either received no back-up or had to call a “code black”, which prompts a police response and usually is reserved for an armed threat.

By contrast, he said code grey calls could be made before violence erupted, allowing a clinically-led team to lessen the tension where possible and minimise risk.

A senior doctor said emergency departments took “chaos off the street” and violence was the predictable consequence when mentally ill, drug-affected, drunk and angry people were concentrated in a crowded, stressful environment.

The ACEM’s Dr Judkins said: “It’s bubbling up around us and we are immersed in it. We just get used to it and I think if someone came in from the outside they would be shocked.

“People just shrug their shoulders and say, ‘This happens in EDs’. If it happened anywhere else there’d be a lockdown, police would be called and the patient dragged away.”

Doctors and nurses agree that one of the major barriers to change is a lack of data on violent incidents. Victoria’s auditor-general last year found the system used by public hospitals to report incidents was “not fit-for-purpose – leading to inconsistent reporting that is of questionable value to management”.

Nurses say it can take 45 minutes to complete a report using the system, which contains mandatory fields irrelevant to reporting occupational violence, often with no follow-up.

Doctors and nurses said hospital boards should receive detailed reports on the nature and extent of occupational violence and be held accountable for their performance by government, as occurred for key financial and healthcare indicators.

There also were widespread calls for well-trained and unarmed security guards to be stationed in emergency departments around the clock, without being called away to other areas of hospitals.

Separate rooms were needed in all major hospitals to accommodate agitated patients and treat them away from other patients, doctors and nurses said.

Mr Wong, who has returned to full-time work as a neurosurgeon but continues two hours of therapy daily on his injured hand, said he hoped the attack on him would lead to greater protection for staff and patients.

“I don’t want to be dead and they hang my photo in parliament and say, ‘This doctor sacrificed his life, let’s do something about it’. I want to be able to speak and push the message forward. All of us will one day be in hospital. We want it to be safe.”

Labor says it will:

Establish a simplified mechanism for hospital staff to report violence.

Compel hospitals and boards to report every violent incident and report data publicly.

Introduce consistent code grey and code black security responses.

Audit security staff in public hospitals and consider “risk assessments, behavioural contracts, client alert systems, training and post-incident response”.

Health spokesman Gavin Jennings says: “Addressing violence in healthcare settings is a priority for Labor and we will have more to say in this space.”

Coalition Health Minister David Davis says his government has:

Established a ministerial advisory committee to improve hospital safety.

Developed guidelines for code grey security responses in hospitals that are “being implemented steadily”.

Audited major emergency departments and upgraded duress alarms and CCTV cameras.

Introduced a system for reporting violent incidents in hospitals. Mr Davis says he is open to the idea of releasing data publicly.

Introduced legislation to increase penalties for offenders who assault health practitioners in the workplace.