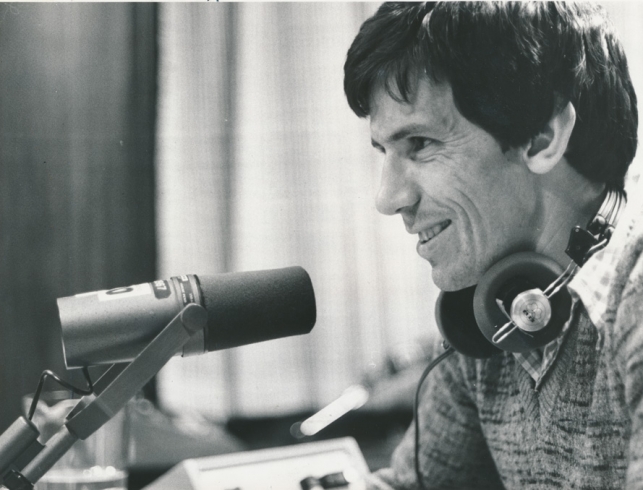

Few league footballers have fitted the stereotype of how players at the game’s elite level should look less than Melbourne champion Robert Flower.

The wingman arrived at the club in 1972 from Murrumbeena looking more suited to a clerical job behind a desk than a leading role on the field. He was built like the proverbial twig at just 68 kilograms, and with poor eyesight sported a pair of decidedly unfashionable “Coke bottle” glasses.

Even Melbourne, to which Flower was zoned, and the club he had barracked for all his life, was at first reluctant to give him a go in the fourths. It would be forever relieved it did. And not only because by midway through his second season in 1973, Flower was already a fixture in the firsts.

In what were the dark days of the 1970s and early `80s for the Demons, their lightly framed wingman provided a rare ray of light for supporters with his brilliant balance, ball skills and capacity to skip through the tightest of packs.

But sadly, Melbourne has lost another legend well ahead of time. Flower, 59, died on Thursday.

Flower’s family released a statement on Thursday night. “It is with the deepest regret that we wish to advise of the sudden passing of Robert Flower, after a brief unexpected illness. The family is devastated by the sudden loss and would appreciate privacy at this time.”

His playing record says much. Flower played 272 games for Melbourne, second only to David Neitz, captained the club for seven seasons, won the 1977 best and fairest, and finished third in the Brownlow Medal. He would be one of the first players picked in the Demons’ Team of the Century.

Many who saw him play would argue that doesn’t do Flower nearly enough justice. A better statement about his status in Victorian football of that period would be his almost permanent selection in state sides.

Flower, like some of his contemporaries who played for unsuccessful clubs, considered donning the “Big V” as a chance to exhibit his skills at the highest level. In effect, the closest he would come to finals, and it was a stage upon which he regularly shone.

But it wasn’t only his obvious natural ability that won universal admiration. Flower was a player who, despite his slender build, boasted enormous reserves of courage, which were frequently required as opposition sides targeted him, knowing that to neutralise Melbourne’s only clear superstar of the time was as good as ensuring victory.

Flower copped all the punishment and continued to shrug it off, regularly playing injured, yet still starring with his loping stride, liking for a goal and strong skills overhead.

At the end of the 1986 season, aged 31, Flower had to be talked into one last season at VFL level, and seemed destined to end his career as one of those unfortunate never to have had the privilege of seeing September action.

But almost as if by fate, in 1987 Melbourne came from the clouds in the latter part of the season to launch an unlikely charge at the finals.

It had been 24 years since the Demons had been part of September, but needing to beat Footscray at the Western Oval in the final round of the season and have other results fall their way, Melbourne did it for the veteran skipper.

Flower, by now stationed on a half-forward flank, repaid those efforts in spades with tremendous performances in Melbourne’s elimination final and first semi-final thrashings of North Melbourne and Sydney respectively, booting five goals then four in those triumphs.

His last VFL game would prove the famous 1987 preliminary final, when the Demons led until after the final siren, when Hawthorn’s Gary Buckenara, aided by a 15-metre penalty, shattered the fairytale.

Flower had already been crunched in that game, his shoulder damaged, and would have been in serious doubt had his team made the grand final. Yet such was his reputation for defying the odds that few would have been prepared to rule him out definitively.

Defying the obstacles of a weak team around him and an always frail build, Flower knew better than anyone how to beat the odds. And he did so with enduring grace and humility.