HEALTH workers are calling for two new hepatitis C treatments to be added to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme as infection rates in the western suburbs increase.

Staff from Hepatitis Victoria, St Vincents Hospital’s Werribee hepatitis clinic, Footscray-based primary care service Healthworks and the Sexual Health, HIV and Hepatitis Education Program used a roundtable discussion earlier this month to urge the federal government to make telaprevir and boceprevir available on the PBS.

Latest data from Hepatitis Victoria reveals that Brimbank has the fourth-highest infection rate in Victoria, returning 65.5 positive tests per 100,000 people in the 12 months to August 2012.

Maribyrnong was third with 68.6 positive tests per 100,000. Melton, Wyndham and Hume also had large populations of at-risk groups.

Western Health hepatitis C service nurse consultant Sally Watkinson believes high infection rates could be attributed to a growing population and high rates of chronic disease.

“We are talking about a demographic which already has a high burden of chronic disease and a rapidly growing population,” she said.

“It’s also a low-socioeconomic community, with a culturally diverse population in need of more health education and understanding of treatments available.”

Ms Watkinson said Western Health held free clinics every Tuesday night at Footscray hospital for marginalised people infected with the disease, including drug users, culturally diverse groups, youth and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander residents.

She said the new treatments needed to be added to the PBS to reduce the number of people waiting for treatment and the number of those at risk of suffering permanent liver damage.

Alex Thompson, head of hepatology research at St Vincents Hospital, said it had been running a hepatitis clinic at Werribee Mercy Hospital for eight months and had noticed an increase in patients asking about telaprevir and boceprevir.

He said hepatitis infections could cause liver failure and liver cancer and were the most common cause of transplants in Australia. “The treatment we have at the moment is OK, with a 40-50 per cent cure rate. The new treatments are doubling [cure] rates,” Dr Thompson said.

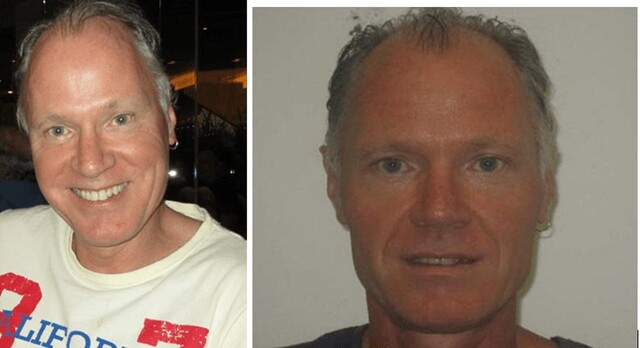

Rose Coulter, who lived with hepatitis C for more than 40 years, said she was disappointed the new drugs were not available in Australia. Ms Coulter underwent treatment four years ago and is now free of the virus. She describes her six months of treatment with interferon as a difficult time in her life, after experiencing pyschological side effects.

“By week 12 I was homicidal and suicidal. I can understand why people don’t complete treatment. I thought the treatment worse than the disease.”

She said making the new treatments available on the PBS would mean fewer people would have to experience what she went through.

“I would like see interferon phased out and the early introduction of the new therapies which have less side effects. I feel very strongly that we need to have access to new virals.”

Prime Minister and Lalor MP Julia Gillard said the drugs had been approved by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee and the government was negotiating a price for the treatments and conducting quality and availability checks.