Australia is grappling with the twin crises of family violence and housing shortages. At the Caroline Chisholm Society (CCS) these two nation-wide issues have come to a head as Hannah Hammoud reports.

The Caroline Chisholm Society – based in the western suburbs of Melbourne – provides wrap-around family services to prevent the need for child protection involvement for thousands of women and their children who might otherwise have entered or experienced the trauma of out of home care.

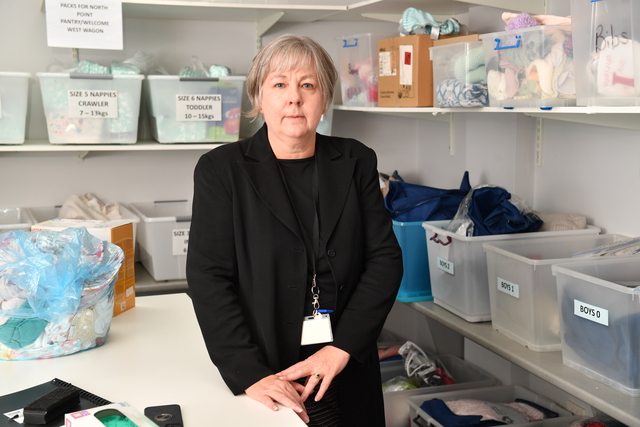

CCS chief executive Jennifer Weber says early intervention and prevention is the key to working towards positive outcomes for vulnerable women.

“We are experiencing a demand for services, particularly for women who are pregnant and impacted by family violence and homelessness,” Ms Weber said.

“We know from research that pregnancy is often a very vulnerable time for women and it can often be the trigger life-event where women start to experience violence.”

Ms Weber said services like the CCS aim to provide essential support to pregnant women, allowing them to self-refer to family services prior to childbirth. The goal is to connect these expectant mothers with resources early on, ensuring their safety and readiness for their baby’s arrival. However, the current surge in demand has meant that pregnant women are often not prioritised until after their baby is born.

This delay can lead to severe consequences. For instance, when at-risk mothers give birth, child protection services may become involved immediately if there are concerns about the mother’s ability to provide a safe environment for the baby. In some cases, mothers have reported being told they cannot take their baby home or continue breastfeeding because child protection has decided to place the baby in care due to perceived risks.

Ms Weber said a common scenario involves mothers who are escaping family violence and have been unable to secure stable housing during their pregnancy. Upon giving birth, they face immediate scrutiny from child protection services. If they are found to lack safe housing, their newborn may be required to stay in the hospital until suitable accommodation is found. This situation forces new mothers into a frantic search for housing, under the pressure of knowing their baby cannot come home until it is resolved.

Ms Weber said funding received by the CCS limits what the organisation can do in the early intervention/prevention space – called the “first 1000 days” – a critical time between a woman’s pregnancy and her child’s second birthday. The first 1000 days represents a time that can be an opportunity for both “tremendous potential” as well as a time of “potential risk of adversity and vulnerability.”

Ms Weber said funding for family services like the CCS is the “loose change in the couch” to supporting this increasingly vulnerable cohort of women.

“We are not asking for millions and millions of dollars but we are asking for the discussion and serious consideration to be given to how we can be funded,” she said.

“There are more than 2000 women in Victoria needing help and there are very limited pathways into services for women. Instead of somebody putting them onto a waitlist, we can start working with them straight away, and we get really good outcomes when we do this because we can move very quickly to stabilise the situation.

“To me, the housing first principle is first and foremost. In the government budgets there are very grand themes that seem to be identified, but what about when organisations are endeavouring to do what these aspirations are trying to solve by coming up with real solutions. But we in fact still can’t get access to respectable housing solutions, and by that I mean not putting pregnant women into hotels that most of us would never want to be staying in, and they’ve got two to three days to stay there and then they’ve got to find somewhere else.“

A state government spokesperson said victim survivors of family violence are prioritised for social housing.

“Housing allocations for family violence survivors have grown by 49 per cent since 2019-20,” the spokesperson said.

“We have also invested more than $72 million in the Victorian Budget 2024-25 to provide immediate support and emergency accommodation for survivors of family violence.“

The Premier Jacinta Allan and Minister for Prevention of Family Violence Vicki Ward recently met with the sector to hear about what is working well and what more we can do to provide emergency accommodation for those escaping family violence.

Ms Weber said the CCS wants the government to enable them to work with women “sooner rather than later”.

“We want them to help us find houses and accommodation that can be available for six to 12 months at least in the short term to stabilise mum’s situation,” she said.

Ms Weber said in the prenatal stage, providing timely support to expectant mothers can be a pivotal moment that changes the trajectory of their lives and the lives of their unborn children.

“I often think of it as a sliding doors moment,” Ms Weber said.

“Consider the case of a pregnant woman who arrives in Victoria from another state, fleeing family violence and other issues. She has been couch surfing, and her Centrelink payments have been disrupted due to her unstable living conditions. In the final weeks of her pregnancy, she visits a Centrelink office to fix her payment issues. During her visit, she starts to reveal more about her situation, which raises red flags. The Centrelink social worker then comes over to speak with her and this is where the sliding doors moment happens. The social worker has a couple of options, they could either flag her case in the system or they could call the Caroline Chisholm Society. Within hours of us getting that call, we’ve set up a practitioner, a doula to support mum during her childbirth, and because we’ve been able to provide wrap around services we can then start addressing housing and other issues and child protection doesn’t need to be involved.”

Ms Weber said this scenario underscores the critical need for proactive support systems for expectant mothers, especially those in vulnerable situations.

Ms Weber said the current system often falls short with many expectant mothers facing delays and barriers when seeking support, sometimes resulting in situations that could have been avoided with timely assistance.

“We need to do better for anyone regardless of their particular situation – not having to sit and wait at intakes to be considered for a few nights of accommodation. But particularly so for a pregnant woman, it’s such a critical time for them as they are about to give birth, if child protection gets that call and has to investigate once mum gives birth… this is not going to be a great outcome.

“If baby has to be removed from mum and go into care, what’s that going to cost? Not just the social and emotional wellbeing of mum and bub, but on the system itself?”