The message read: “Send me a pic without your clothes on”.

Its sender was a teenage boy, a family friend of the recipient, who was a child of 12.

Sarah* was in grade six at a primary school in Melbourne’s western suburbs, and was playing on an iPad when she received the message.

Fortuitously, she was sitting on a couch next to her mother, who happened to cast a cursory glance at the screen just as it popped into view.

“It was just really lucky that Jane* was in the room,” Sarah’s school principal, Michelle*, said. “It was a really provocative message.

“Sarah didn’t understand the subtext … you just have to be so careful.”

She said the offending teenager had previously been in a relationship with another minor, who had then become pregnant.

Sarah’s message was referred to Victoria Police, and all parties have received counselling.

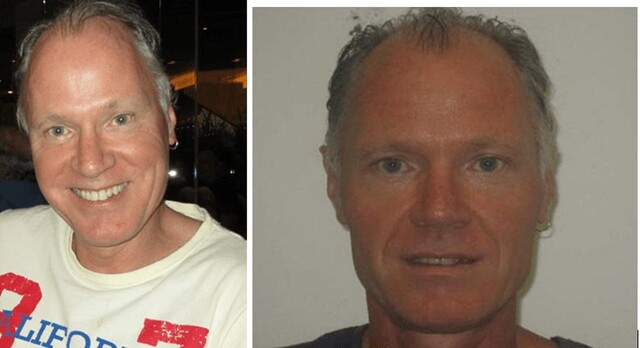

Australia’s leading cyber safety expert Susan McLean said the incident, which happened last year, is not an isolated one.

Ms McLean said the proliferation of electronic devices into every facet of daily life, including classrooms, has forced parents and schools to step-up their efforts to educate children about safe and respectful behaviour online.

She said schools needed to inform teachers, parents and pupils about cyber safety, so they can be aware of the dangers, such a cyber bullying and the grooming of minors by sexual predators. Their obligation to inform the school community isn’t just a moral one, she said.

“Schools have a legal obligation to deal with any online issue they are informed about, no matter when or where it happens. So if you’ve got kids being cyber-bullied at night and you’re told about it, you have to deal with it.

“If you put in place some education to try and prevent that, you’re going to save yourself a whole lot of heartache in the long-term,” she said.

Ms McLean, a former police officer, said many parents are unaware that the minimum age to open a Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or Snapchat account is 13, and 18 for YouTube.

“Parent education is vital, and it must be delivered by qualified experts, not by people who have an interest in cyber safety.

“Schools need to have really clear rules and boundaries in place, so that children and parents are very clear about what is expected of them.

“I deal with schools where parents are bullying teachers, parents are bullying other students, so policies needs to encompass the whole school community, not just the teacher or not just the child.”

She said cyber-bullying and exposure to pornography often starts in grade two, while the sharing of naked and semi-naked photos is not uncommon among grade fives and sixes.

Her experience is backed by new state government data that shows there has been an increase in reports of incidents of sexual behaviour in Victorian schools over the past 10 years, with the number of alleged incidents rising from 132 in 2006 to 258 last year.

To counter the problem during school hours, many primary schools have banned electronic devices, such as mobile phones, outright.

Ardeer South primary school principal Peter Guest said pupils whose parents insisted their children have a mobile phone were required to leave them at reception at the start of each school day.

“If they (students) are hooked up to the internet, you don’t know what they’re looking at,” he said.

Mr Guest said parents were informed about how they should approach “screen time” at home through the school’s weekly newsletter, and also as part of student induction.

He said the problem is unsupervised use.

“That’s when kids get into trouble. My rule is that parents should always be able to see the screen,” he said. “And I think any parent who allows screens at bed time is asking for trouble.”

Alamanda College at Point Cook has just rewritten its mobile phone policy, rules banning the devices from the classroom for years 7, 8 and 9 students from next year.

Principal Lyn Jobson said research supporting mobile phone use at the secondary level as part of the curriculum was outdated.

“That research has changed,” she said. “It now says it’s impacting their mindfulness, their brain chemistry and their focus.

“We tried to go with the ‘let them use it’ approach, but they [mobile phones] were a constant distraction … so as of next year, they’ll have to keep them in their lockers.”

She said teachers had expected a pushback from students about the new rules, but there had been none … “the kids actually agreed”. She said some students already voluntarily handed in phones to avoid distractions in class.

The school also communicates with parents about “close-off time”, when all electronic devices are banned at home, and “blended time” – parent supervised Internet use.

“You can’t assume they’re in their bedroom doing something cute,” Ms Jobson said.

* Names have been changed to protect identities.