Before the early 1990s, it was common practice for motorists driving along the Princes Freeway to wind up their windows as they passed Werribee.

You could count on a southerly breeze pushing the odours from the Werribee sewage farm northwards up until about 25 years ago when massive covers were installed on top of its main sewage lagoons.

Since then, the sewage facility, now called the Western Treatment Plant (WTP), operates like the well-oiled machine it is – just without the smells.

It’s been there almost 125 years, having been built when the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works was set up to manage the city’s supply of water and treatment of sewage.

Under the guidance of chief engineer William Thwaites, construction of a sewage system began at Werribee in 1892, with a pumping station at Spotswood. Just five years later, the first Melbourne homes had their effluent transported all the way to Werribee with just a single flush.

WESTERN TREATMENT PLANT MANAGER MARTIN BOWLES.

Now the plant serves more than 1.6 million people in the central, northern and western suburbs, and all it takes is 30 to 35 days for raw sewage to be recycled or discharged into Port Phillip Bay.

WTP manager Martin Bowles took Star Weekly on a tour to show how a little more than half of Melbourne’s sewage is treated and explain the other uses Melbourne Water has for its 10,500-hectare site at Werribee.

“Sewage is now thought of as a resource … It will become a source of revenue.”

It’s a grey, drizzly Melbourne morning as Bowles drives towards the open-cut drain where the city’s raw sewage enters the plant. The drain opens up on the property – which is equivalent in size to Phillip Island – alongside an “odour control facility” that removes hydrogen sulphide, or rotten egg gas, before the sewage flows along a 17-kilometre drain and then into 10 treatment lagoons.

Surprisingly, peering down into the drain wasn’t as visually off-putting as anticipated. The equivalent of 180 Olympic-sized swimming pools full of sewage is pumped to the treatment plant each day. But, as Bowles points out, the contents are 99 per cent liquid … it’s not just human effluent but waste water from washing machines, dishwashers and kitchen sinks.

And it’s already been through giant macerating pumps that break solids down.

From there we drive to the main treatment lagoons, or as Bowles calls them, “fart tarps” – ponds covered in high-density polyethylene that suppresses foul smells, halves greenhouse gas emissions and captures methane gases. “The covers starve the contents of oxygen, and bugs eat away at the solids that form on top,” he says.

AERATORS PUMP OXYGEN THROUGH PARTIALLY TREATED SEWAGE IN A PROCESS NICKNAMED ‘THE MILKSHAKE’.

A contract was signed with AGL in 1998 to harness the gases trapped under the tarp to produce electricity. This now generates almost 95 per cent of power used at the plant.

Bowles says works are under way to expand operations so the plant can produce more energy than it needs and begin exporting it back into the grid.

“Sewage is now thought of as a resource,” he says. “It will become a source of revenue.”

From here we’re driven to the aptly named “milkshake machine”. Thousands of bugs swarming just beyond the safety of the car door warn of the smell to come. We’re at the “activated sludge treatment plant”, where huge rotating motors aerate the sewage to remove its high nitrogen content into the atmosphere.

Without this step, organic nitrogen and ammonia would be deposited into the bay, turning it a sickly shade of green.

https://youtu.be/y9uRiRYGdik

VIDEO – COCOROC; THE LITTLE OLD MELBOURNE TOWN YOU PROBABLY NEVER HEARD OF

Occasionally the motors will fall off their shaft, requiring a “poo diver”, as Bowles calls commercial divers, to dive into the sludge and fix the mixer.

“Poo-diving, it’s a thing,” he says with a laugh. “There’s zero visibility, but they get suited up.”

From here, the sewage flows through 10 lagoons, becoming clearer and cleaner as bacteria breaks down the organic matter in the water making its way either into the bay or to be used to irrigate vegetable crops.

Bird watcher’s paradise

At the edge of the property, where the last lagoons run out into Port Phillip Bay, it’s difficult not to be impressed by the variety and sheer number of birds that come here to feed. Bowles says it’s testament to the cleanliness of the recycled water. “For me, the judge of water quality is the birdlife at the end.”

He points to the pelicans, swans, terns and shore-line birds that have gathered in a cacophony of noise at one of the bay outlets.

“The birds love the nutrients left in the water. This place has gone from being declared a wildlife sanctuary in the 1930s to a Ramsar- listed site.” (The Convention on Wetlands of International Importance – the Ramsar Convention – was signed in Ramsar, Iran, on February 2, 1971.)

TRACTORS SCOOP UP DRIED BIOWASTE FOR STORAGE UNTIL AN ENVIRONMENTALLY SOUND USE IS FOUND FOR IT

It’s considered the second-best bird-watching site in Australia (after Kakadu) and for just $50, and a $50 key deposit, you can purchase a two-year bird-watching permit to go there.

Mr Bowles says there’s no shortage of bird-watchers coming to catch a glimpse of some of the world’s rarest birds, including species that migrate from as far away as Siberia.

Back at the 10 eight-metre-deep lagoons, Bowles explains that each one has to be dredged every five years.

The solids that settle at the bottom are moved to “sludge-drying pans”, where they are ploughed to remove any liquids then excavated and made into mounds of biowaste, which are currently Bowles’ biggest headache. Recently, Melbourne Water trialled turning this byproduct into bricks, but they lacked the structural integrity to hold their shape.

“We have mountains and mountains of biosolids,” he says. “It would be a fantastic fertiliser were it not for all the metal in it.”

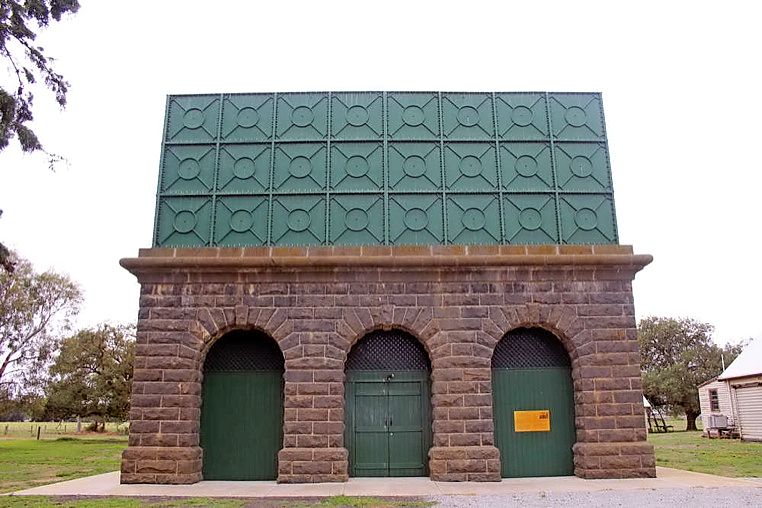

THE ODOUR PLANT WHICH TAKES GASES FROM THE INCOMING SEWAGE AND ELIMINATES THE SMELL ONCE ASSOCIATED WITH THE PLANT AND WERRIBEE.

It’s hoped WTP’s partnership with universities will speed up a solution.

Ghost town

Our last stop is the former hub of Cocoroc, an abandoned town built to house MMBW staff and their families in 1894. At its peak, the community numbered 500.

Houses were moved or destroyed in the early 1970s, and the four primary schools are now gone, but the old football ground, a town hall and an empty outdoor swimming pool remain. “Cocoroc, that’s the sound the growling grass frog makes,” Bowles says.

The name also means frog in the traditional language of the Wathaurung people, traditional owners of WTP’s land.

As we head back to WTP headquarters, Bowles points out rows of healthy-looking corn crops. Six years ago, Melbourne Water signed a 20-year contract with MPH Agriculture, a privately owned agribusiness, to farm 5000 hectares of the property for livestock feed and take up other ventures.

Bowles says it costs $20 million to run the plant each year to treat more than 50 per cent of Melbourne’s sewage. To put it into context, it’s the same amount Premier Daniel Andrews spent last year to attract investment and visitors to the state.

This year marks the plant’s 125th birthday. And while it might still be called a “poo farm”, this is a milestone Victorians should consider next time they find themselves on the Princes Highway with the windows down.