“Are you here about what happened last night?” Julie asks from behind the glass.

It’s a balmy December evening in St Albans and the Weekly has come looking for the railway station’s last line of defence: two Protective Services Officers going by the names of Kevin and Kuldeep.

The duo are among 586 PSOs working across 82 stations.

Julie spent much of 2013 sitting behind the protective glass of Metro’s St Albans ticket booth after moving from North Melbourne, and she’s noticed a calmer environment since PSOs began patrolling among the swarm of commuters who flow through the station between 6pm and the last train each night.

Despite an Australia New Zealand Policing Advisory Agency survey released last month that revealed a significant decline in Victorian commuters feeling safe on public transport (24.2 per cent) compared to 2008-09 figures (27.9 per cent), Julie believes there’s been a positive change.

“A few people say to me they feel safer [at St Albans station]. There’s been quite a few issues.”

Like last night’s armed robbery when two PSOs helped police chase down a pair of would-be thieves at a supermarket across the street.

While the PSOs’ lines of enforcement outside the station are intentionally vague, assisting police is one of the tasks required alongside their chief concern: creating an atmosphere of safety. In that sense it’s been mission accomplished, although Julie would like to see the state government go a step further and staff PSOs from “the first train to the last”.

She’s not naive enough to think local crime has been curbed, though. It’s just moved to another location, or to an earlier time slot.

“Drug and alcohol-affected people don’t have a time frame,” she says. “It just means the crime happens earlier in the day.”

A wave of commuters bustle through the station’s sliding doors, and among them are the PSOs the Weekly is seeking.

“Checking tickets isn’t our primary concern, safety is,” Kuldeep says when asked to define his new role overseeing the transportation of this community: refugees, the unemployed, workers, those on low incomes, the high, the low and the just plain drunk and restless.

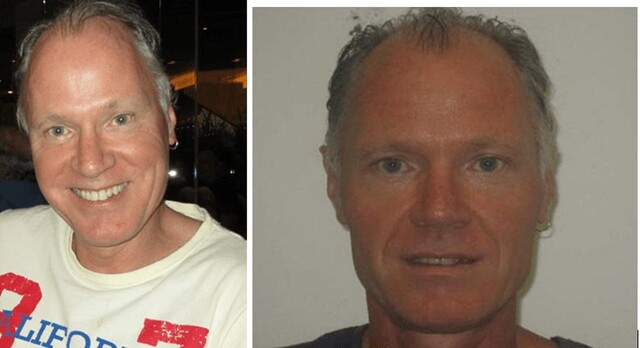

“The crime has moved away from the station, and onto the trains … to other areas and to other times,” adds Kevin, who at age 41 left a much safer desk job in computer science in January to patrol both here and at Watergardens station. His girlfriend was not impressed with his career change.

In November, a Fairfax Media report revealed assaults and thefts at railway stations hit a five-year high in the first year PSOs were deployed.

“She was scared at the time,” says Kevin. “She was always thinking the worst-case scenario, that I might get stabbed, bashed or shot even. But it’s been alright, she’s sort of adjusting. It’s mostly assaults and petty crime [you deal with]. I enjoy the direct contact I have with people. You can see the impact you have on the community.”

Kuldeep is in no doubt he made the right move giving up his job as a door-to-door salesman with Telstra.

“I love my job, mate,” he says sincerely. “Ninety per cent of people don’t have a problem with us; 10 per cent do.” From escorting the overindulged into ambulances to busting serial fare evaders with outstanding warrants, the work is niche but rarely boring. PSOs have also reported incidents where they had to talk people around from attempting suicide.

Praise for their work has been rare, yet some has come from unlikely sources. A few months ago, Kevin says he was approached by a career criminal.

“This guy was a crook with a long history of crime, and he comes up to me and says, ‘I don’t like you guys, I don’t need you, but I now realise my kids need you’.”

Both PSOs say they have built a rapport with their travelling community.

As we watch a train disappear into the distance, a female commuter on her way home from the gym comes over for a 10-minute chat. She’s probably not one of the 51.2 per cent who said in the survey they felt safer walking home at night than on public transport.

Asked about his method of charming more difficult members of the public, Kevin says: “I use the attitude test. I usually give them a warning if they give me no lip. If people admit their mistake we let them off.

“There was one kid who jumped onto the tracks to cross to the other side, just before a train came. I said, ‘What did you do that for?’ And he said he had to go to the toilet.”

Kevin smiles, but admits it’s not so easy with the drunks. “We don’t let the drunks off. We can hold up the train if we have to. We had to drag a guy off the train once because he was drunk.”

Armed with all the tools of the standard police officer – handgun, baton and capsicum spray – these two take on a handful of incidents for each 10-hour shift and, on average, make one arrest a week.

“There was one guy, a regular on the line, who was assaulting young girls,” Kevin says. “He was asking girls to be in photos with him, you know, selfies, but he was grabbing them on the breasts. He was in his 70s.”

Kevin says PSOs have essentially wiped out response times to train station crime. “We can get involved in an incident straightaway,” he says. “And people have somebody to tell straightaway … before, when the police arrived they were picking up the pieces.”

He’s not surprised there’s been a spike in assaults (716 up from 645) and thefts (472 up from 352) at stations over the past year. “A lot more is being reported and recorded.” However, robberies at stations have dropped from 184 to 126.

Suddenly, a group of young men sprawled on the ground on the opposite side of the tracks catches Kuldeep’s attention. One in particular, is slumped against the fence with a hat pulled down over his face.

“We better check this one out,” he says to his offsider.

As we cross the tracks, the Weekly points out four men drinking under some trees across the road. One sits in his wheelchair with beer in hand. “Oh, yeah, there’s going to be heaps [of drunks tonight] …” Kevin says.

It turns out the young man is only resting in the heat after a hard day’s shopping, and what looked like a slab of beer at his feet was only a case of tinned vegetables.

It sums up a quiet shift so far.

“Ninety-nine per cent of the time there’s not much that happens … and for the other time that’s when people need ya. But I’d like to see PSOs [working at stations] all the time; it has to happen eventually,” Kevin says.