It ain’t rocket science, but Lachlan Thompson’s new job has endless possibilities. After a lifetime of exploring the world of science, Thompson will ponder even bigger questions as an Anglican deacon. And he is certain the two roles can co-exist.

Thompson, 61, will combine his RMIT professorship with his pastoral duties.

“I’ll be a rocket scientist Monday to Friday, five days a week, and Sunday I’ll be ‘priesting’,” he says. “I guess that makes me the Rocket Rev.”

As a child of the 1960s, Thompson was fascinated by science and religion. Growing up near Essendon Airport, he could identify plane types by their engine noise. The space race was also unfolding around him.

When he was five, Thompson watched the Melbourne night sky as the USSR’s Sputnik 1 orbited the earth to broadcast radio pulses. “I remember dad picking me up and pointing to the sky,” he says. “It was a silver dot.”

Thompson’s late father, Arthur, worked for CSIRO and showed him grainy 35mm footage of the new Parkes radio telescope. When Thompson was seven, they built their own.

“I remember helping him grind the mirror on the kitchen table,” he says. “It took weeks and weeks. We’ve still got that telescope to this day.”

With his father, late mother Myrtle and younger brother Robert, now a computer-security expert, Thompson attended the local Presbyterian church and later the Anglican church through a youth group.

After watching the first moon landing in 1969, Thompson worked as a technical officer with the federal government’s Aeronautical Research Laboratories with the late Dr David Warren, who invented the aeroplane black box flight recorder.

Thompson then studied aeronautical engineering at university and returned to work on missiles and planes such as the Nomad and Jindivik.

“I did the aerodynamic design in an anti-missile or missile defence system … called Nulka,” he says.

After 15 years with the government, Thompson joined RMIT as an academic, teaching and returning periodically to the industry. Since the late 1970s he has taught countless students and supervised projects such as Glen Waverley Secondary College’s groundbreaking Spiders in Space.

After winning an Australian competition, the project aimed to see how spiders wove webs in space, but they died with the crew when the space shuttle Columbia tragically exploded in 2003. Thompson and the students continued their work, expanding it to include bees.

He has also taken students to the International Space Olympics in Moscow, where two teenage girls from Melbourne – who were on the verge of dropping out of school – became the first winners from outside Russia for their work on how blood clots are affected by different atmospheric conditions.

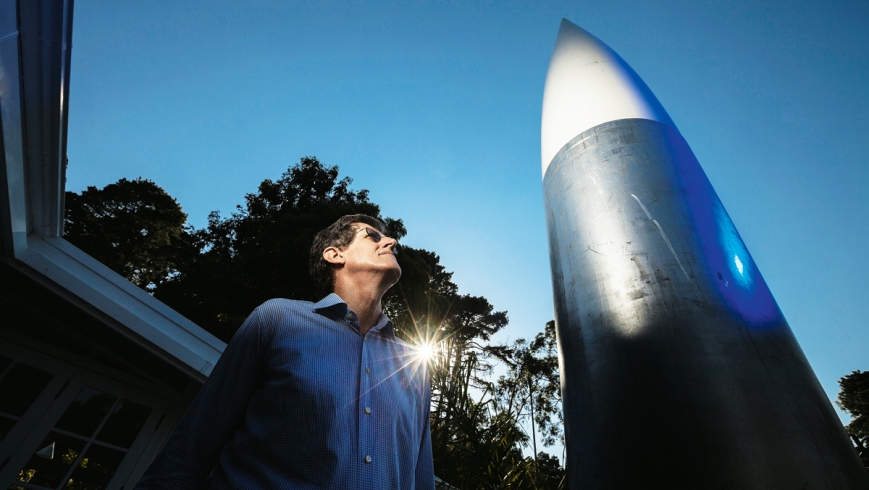

Over the past five years, Thompson has worked with RMIT students to build a space rocket they hope to launch, carrying a satellite, within 10 years. The 11.5-metre rocket, which students work on as

part of their course, is at RMIT’s Bundoora campus.

The goal is to have it orbit the earth at 250 kilometres. It would be the first Australian satellite launch since the federal government launched a purchased satellite in 1967. Australia has achieved very little in the field since. This disappoints Thompson, who says countries such as Canada have experienced the economic benefits of space programs by selling spin-off technology such as robotics.

Given recent federal government cuts to the CSIRO, Thompson says Australia is way behind. “It concerns me that Australia is going to become irrelevant in the space-technology field,” he says. “We need … to become an intellectual-property developer.”

Over the years Thompson’s religious faith has been tested, not by government priorities or failed experiments but by the Vietnam War, the loss of his first child, Katherine, to leukaemia as an infant, and two friends dying in hang-gliding accidents within months of each other. But his faith survived, and Thompson recently completed a graduate diploma in theology.

“I worked out that … if God intervened and actually changed things for people, you would end up in a world of absolute chaos,” he says. “It would always be completely turned upside down. God basically doesn’t intervene. The biggest intervention was Jesus Christ.”

Thompson has also reconciled science and religion. “You can … worship God and you can enjoy that relationship and you can be a successful scientist and a successful engineer,” he says.

Once ordained on February 1, Thompson will do just that. He has had nothing but support from colleagues, sons Stuart, 30, a computer engineer, and David, 28, who writes computer games, and his second wife, Annie. As a deacon, he will lead services and preach sermons at St Thomas Upper Ferntree Gully on Sundays, assisting priest Raffaella Pilz with communion. He hopes to be ordained, and plans to wear his clerical collar to work and counsel colleagues and students if needed.

“It’s a chance to basically enjoy and celebrate one’s Christianity; it’s fantastic,” he says. “It’s a real buzz.”

ccritchley@theweeklyreview.com.au