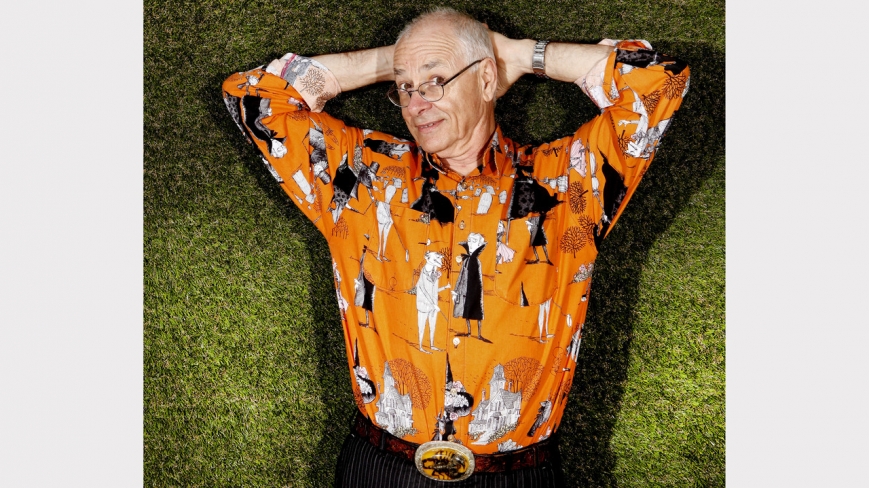

It’s not often you meet someone who has a planet – one that oscillates in an orbit between Mars and Jupiter, as it happens – named after him, but then it’s not often you meet someone like Dr Karl Kruszelnicki.

“It’s a minor planet,” he says. “I might have spoken softly when I said the word ‘minor’. It’s a planet called 18412, registered with the International Astronomical Union. It’s probably around 20 kilometres in diameter. I hope like heck it doesn’t wipe out all life on Earth as we know it with some sort of freak accident. It’s twice the size of the one that wiped out the dinosaurs.”

It seems there’s no topic on which Dr Karl does not have an interestingly expressed opinion. He even asks me to stick my head against the glass of the elevator at the ABC in Southbank to admire its hydraulic beauty.

He has channelled some of his knowledge into a new book, Game of Knowns: Science is Coming, which includes explanations about how smartphones dumb down our conversations, why we drink beer faster when it is served in a curved glass and why the left side of our face is the most attractive. “It’s a handbook for the 21st century,” he says.

To say that Dr Karl has had a varied career is an understatement. After school at Christian Brothers in Wollongong, he laid pipes for a while, then studied physics and maths. By 19 he was working as a physicist and later as a scientist in Papua New Guinea and as a filmmaker in Sydney. From 1972 to the mid-1980s he moonlighted as a taxi driver to beef up his income from various jobs, which included working as a mechanic for a while.

“I felt it was ridiculous that I knew how the universe began but I couldn’t fix my handbrake,” he says.

He has also worked as a roadie for Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry on their Australian tour, a TV weatherman, a doctor at Sydney Children’s Hospital (he somehow managed to fit in a medical degree) and as a biomedical engineer for Fred Hollows, designing a machine that picks up electrical signals from the human eyeball. “My career has been like a Paddle Pop stick in the gutter on a rainy day. I had no control over it.”

In 1981, when the US was preparing to send a shuttle into space, Dr Karl rang the Sydney radio station then known as Double J to offer his services for a show it was making about the event. The station accepted, and that was the beginning of three decades of bringing science to the mainstream and a life in the public eye.

His CV since then makes you wonder if he ever rests: making his TV debut in 1985 as presenter of the first series of Quantum, talking to about 300,000 listeners each week on his Triple J Science Talkback show, writing 34 books, and running (unsuccessfully) for the Senate in 2007. In 2003 he was named Australian Father of the Year, in 2006 he was made a Member of the Order of Australia and last year he was declared a National Living Treasure.

“I call myself a suboptimal polymath,” he says. “A polymath is good in each of the fields. I was never good at anything in particular but I cover a broad range of fields and dive into them enough to be able to know what’s going on and then explain them to somebody. As a doctor I’m sure I wasn’t incompetent. I wasn’t the world’s best doctor by a long shot. But at least I could help people.”

Karl Kruszelnicki, 65, was born in Sweden to Polish parents. He came to Australia when he was two and spent three years in a refugee camp near the Victorian/New South Wales border. “I grew up in a hut that was the size of a white tradie’s van,” he says. “I’ve got one memory of that time, which is that the family got one egg a week and my parents gave me the egg. That’s what parents do. I didn’t realise this until I was older. And I had this incredible feeling of being loved and thinking what sort of things parents do for their children.”

His father Ludwik, who died in 1980, and his mother Rina, who died 10 years later, were in concentration camps, his mother in Auschwitz in Poland, and his father in Sachsenhausen in Germany. “I went to Sachsenhausen last year,” Dr Karl says. “It was the weirdest thing, to walk across the ground knowing you were walking across the ashes of thousands of dead people. I walked across the camp many times to make sure that I would have intersected with my father’s footsteps at one stage.”

As a young “refo” growing up in Wollongong, Karl always felt like an outsider. “There were the Catholics and the Protestants, and if you weren’t in either tribe you must be something else, so I was a wog. I felt bullied, but it was all I ever knew so I didn’t mind. Everything you could possibly imagine I was bullied (about) at school.”

I ask Dr Karl how this shaped him. “Sympathy for people who get bullied. I was doing a book tour two years ago in Melbourne. The driver seemed like a happy guy and I got talking with him. Turns out he was a Kurd. Every year of his life that he could remember someone tried to kill him and his family, and he became a refugee in Australia and he loves it because no one is trying to kill him. It’s not much to ask for. So I have sympathy for refos.’’

With his wife Mary he has three children, a 25-year-old son who works for a hedge fund, a 23-year-old daughter doing a course in fashion and design technology – “as a result I now know what a circle skirt is” – and a 15-year-old daughter in year 9 at high school.

“Mary was the only girl in a large family of boys, so she had lots of parenting skills. Thank heavens, otherwise I would have been stuffed, I had no idea. The buggers wouldn’t sleep until the age of five. None of them. Aaaarrggh. We watched a lot of Hitler and Stalin World War II documentaries because they were on at 3am.”

Outside work and family, he likes exercising and riding his bicycle, during which he sees some dumb acts. “I saw a driver run into another car the other day while they were texting. Idiots! Having worked in casualty, I’ve seen how people can have their whole life ruined by a single act.”

Cycling keeps him fit. “I came across this paper that said provided you continue to do the same exercise, you never get weak. People as they get older get weaker, but if you look at people who do exercise they lose a few per cent in their 40s and a few per cent in their 80s. But basically in their 80s they’ve got 90-95 per cent of what they had in their 20s, providing they use it. Your body is a flexible, dynamic, plastic thing that responds to the environment.”

He asks me what exercise I do and I say surfing. “Single fin?” No, three fins. “So instead of accepting the goodness that the ocean has to give, you fight it. So the wave is coming and instead of accepting the oneness of the wave and enjoying its beauty you chop it up, go up, go down, that’s why you need your multifins.

“I was talking with Tim Winton the other day – I got him to autograph a copy of his book for my wife – and I asked him what his position was on this and he said he bases his surfing and moral and ethical guidelines on a bumper sticker he saw in the USA – ‘One God, one ocean, one fin’.’’

Dr Karl has long been revered for his work on radio Triple J, making science accessible. I tell him a friend told me she and her friends who listened to Triple J used to call him “God”.

“I think my brain is deficient because of my need for praise,” he says. “Need it all the time.

“Most people got enough praise at kinder when someone said, ‘You’ve done a really good job colouring inside the lines, that’s really good’. And for them that was enough praise for their whole life. Whereas I need praise all the time. If I go on a supermarket shop, I will go down every aisle and typically someone would come up and say, ‘Hi Dr Karl, thanks to you, I’m now…’ and they insert something. They’ve changed their life in an intellectual endeavour because of me on the radio – ‘Because of you I’ve decided to become a chippie’ or ‘I’m going to finish off my school certificate’ or ‘I’m going to do my PhD’ or ‘I’m going to become a nurse’. I don’t know what it is about answering questions on the radio, but it makes me feel really good.”

To what does he trace this desire for praise? “Maybe it was because I was bullied for so many years and now I’m saying, ‘I missed out on having friends when I was a kid’ – and if we had some of those cocktails with umbrellas in them I could spend many hours telling you how unhappy my childhood was.”

Well, he certainly survived this sad youth and prospered. It seems he has excelled at almost everything to which he has turned his hand. As a labourer he holds the record for 50 metres of sewer pipe laid in one day, in Dapto, outside Wollongong, at age 16. In 1972 he worked as a roadie for American guitarist Bo Diddley. “He taught me for (every audience), ‘It’s their first time’.”

Even as a taxi driver he managed to stand out. “I loved taxi driving. I used to be really shy because I’d been bullied all those years. And then suddenly it was my living room they were coming into. “People would start talking and I’d get their names and I’d say, ‘Are you guys married?’ and they’d say, ‘Yeah’. I’d say, ‘I don’t think you guys are really suited for each other because you seem so fundamentally at loggerheads. Did you guys get together as a result of a one-night stand?’ Imagine someone saying that to you.

“I’d never make eye contact and it was at night and I was driving and I got away with it. Some would say, ‘You know what? I half agree with you’ and the other one would say, ‘What? Well, I didn’t want to bring it up but I don’t think we’re compatible’.”

What a fascinating man. Brilliant, engaging, unpretentious and non-jargony. No wonder he’s been so loved these years. Doesn’t his head spin knowing all this stuff?

“Sometimes I have difficulty answering a simple question because I can see so many possibilities. Somebody will say, ‘Are you free next Wednesday?’ and part of me is thinking … ‘Do you want me for lf an hour, 10 minutes or 10 hours? Do you want me to work or do you want me to say hello?’ I can see all these possibilitiesanching off so sometimes I find myself stuck for words.”

Not today.

Game of Knowns: Science Is Coming by Karl Kruszelnicki, Macmillan ($32.99)