Rohan Moore was at home looking after his two children on the day of the car crash. His pregnant wife Lauren was on her way to a birthday party – her father the designated driver – when a motorist ahead took an illegal U-turn across double white lines. There was no chance to stop.

Mr Moore says he remembers the aftermath as though it happened yesterday: the injuries to Nicole’s neck and back; the emergency caesarean section to deliver their premature baby, Grace; her bones broken from the impact. Above all, he remembers the moment Grace died in their arms after the gut-wrenching decision was made to take her off life support.

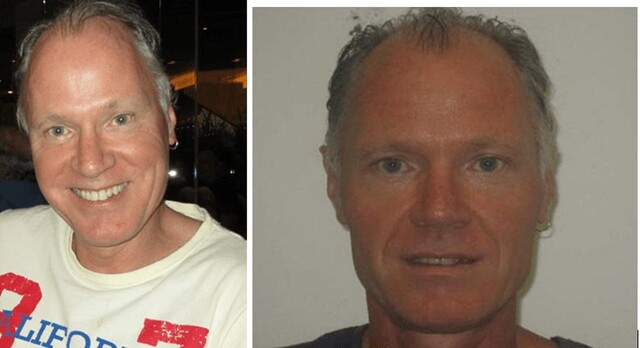

The 35-year-old father says he suffered trauma, pathological grief and adjustment disorder because of the incident. But under changes to the Transport Accident Commission scheme, to be debated in Parliament this week, people like him will find it much harder to claim compensation for severe long-term mental illness.

“Both my wife and I lost our daughter, and for the government not to include me means I’m not being recognised,” he said. “The money doesn’t bother me. It’s more about the trauma and the ongoing impact. It’s like rubbing salt in the wound.”

Among the proposals, for the first time there will be a clinical criterion for what constitutes a severe long-term mental injury or behavioural disturbance. To qualify for compensation, people will have to prove that, for at least three years, they sustained a “recognised” mental illness or disorder as a result of an accident. They also have to prove they did not respond to treatment over that period and their relationships, social life and work have been severely impaired.

Psychiatrists have written to the government warning that the changes will make it almost impossible for anyone to lodge a successful claim. Apart from the definition being too limited, they say the notion of a mental injury over a “continuous period” does not take into account the fact that mental illness, by its nature, tends to fluctuate.

“The wording of the legislation is so severe that we think no one will be able to succeed,” said South Yarra psychiatrist Nigel Strauss.

Opposition Leader Daniel Andrews described the changes as a “cruel attack” on the rights of victims of road trauma, while Maurice Blackburn lawyer John Voyage said: “If the changes to the TAC laws go through as they stand, it will be very hard for someone to qualify as seriously injured for psychological/psychiatric injury, no matter how terrible the accident or events they witnessed.”

Assistant Treasurer Gordon Rich-Phillips defended the move, pointing out that people could still claim under TAC’s no-fault scheme, and that counselling for victims’ families would increase under the legislation. He said the reforms were necessary to stop people exploiting loopholes in the system and to “ensure that compensation is going to people with injuries”.

“The community accepts that if you’re in a car accident . . . you’re entitled to compensation,” Mr Rich-Phillips said. “I don’t know if the community would be entirely accepting if you weren’t in an accident, but you make a claim relating to someone else’s accident.”