STORIES make sense of history and that’s exactly what Olwen Ford intended in her most recent profile of the people of Sunshine.

Harvester City – The Making of Multicultural Sunshine 1939-75 highlights the richness of a community as it transformed from a largely Anglo-Celtic, semi-rural population to one of Melbourne’s most multicultural areas.

Mrs Ford, a historian and resident immigrant herself, also wrote Harvester Town: The Making of Sunshine 1890-1925, and has received awards for her local history work.

She said her latest research tracked the stories of the many waves of migrants and refugees exiting war-torn Europe after World War 2 until just before the end of the Vietnam War in the mid-1970s.

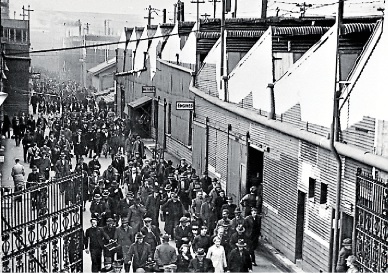

“The book tells the stories of migrants who came to work in Sunshine at a time when the city was home to some of the country’s most important factories,” Mrs Ford said. “It’s full of real-life accounts of war and peace, migration, the pioneering days of the 1950s, factory life, religious faith and the challenges of this area.”

More than 50 local stories are woven through the 36 chapters of this insightful look into the growth of the west and its unique identity within the fabric of Melbourne.

Many storytellers contributed photos from family albums and these are used extensively throughout Mrs Ford’s account of the immigrants who founded modern Sunshine. “People came here because there were jobs for them, and land was not so expensive,” she said. “Also there were two large migrant hostels here, one in Brooklyn, the other in Maribyrnong.

“Brooklyn mainly took the Brits and housed about 700 people, while Maribyrnong, which averaged about 1000 people, took people from the work camps of eastern Europe, Ukrainians, Latvians and Lithuanians.”

She described the 1950s as a key period for migration, with major influxes of Greeks and Greek Cypriots, Maltese and Polish.

Mrs Ford said it would be hard for people now to imagine Sunshine in the early ’50s. She describes shacks built of packing cases and corrugated iron shanties, and people paying a shilling for a bucket of water and using empty tins to scoop water from puddles.

“There was no infrastructure. It was up to local government and individual efforts to build the schools and roads and connect the water and electricity.

“Sunshine in the 1950s was a new housing area. People were allowed to buy a block of land, but they lived in primitive conditions and housing was very rudimentary.”

By the late ’50s, bricks and mortar started replacing the shacks as people put down roots and found work.

“In the 1950s, Sunshine was one of the main industrial areas of Australia,” Mrs Ford said. “Now there’s hardly anything left.”

The famous Harvester factory is now Sunshine shopping centre; ICI became Orica, which will soon move to Deer Park. Nettlefolds, Australia’s biggest nuts and bolts manufacturer, became a Harvey Norman store; Spaldings is now a Bunnings store; while the ETA nuts factory was recently demolished. “Writing the book, I developed a greater appreciation of the ways migrants have sought to maintain their own cultural traditions while also embracing Australian culture,” Mrs Ford said.

The book will be launched tomorrow by Deakin University professor Don Gibb. He said the book portrayed “a very distinct local history” that shed much light on Australia’s post-war manufacturing and immigration.

The book, published by Sunshine and District Historical Society and partly funded by the state government’s local history grants program, costs $45. It’s available from the Harvester library’s interpretive centre on Wednesday afternoons or from Sunshine Newsagency. More details: 9312 2284