Even unconditional love is challenged when children’s drug addictions take over their lives. Ben Cameron meets a group of women who are finding out that sometimes love means letting go.

IT’S four days after Mother’s Day on a chilly Thursday night in Darley, and four women have come together in a nondescript council building to talk about their children’s drug addiction, and their own emotional and physical retreat.

New support group Family Drug Help has been running for a few weeks before the Weekly is invited to hear the stories of this emotionally battered, but not broken, quartet.

It’s already proven to be a major breakthrough for these self-confessed “addictees”, providing the first real opportunity to share their experiences with people who truly understand their daily battles.

The group is moderated by ‘Amber’ from Bacchus Marsh. A recovering addict and mother, she proudly announces that, from two days ago, she’s been clean for 11 years.

“I should have baked a cake,” one of the women quips, as this already-tight group breaks into laughter then applause.

None of these women would be here without Amber’s initial bravery. A few months ago, she outed herself to more than 200 people at a community meeting about ice addiction. She opened up her soul about how drugs can turn friends into enemies, family into foe.

The group was eventually pulled together by Bacchus Marsh police youth resource officer Jim Ross, following requests from parents to do “something for us”.

Tonight’s theme is “Detaching from Love” – a method for dealing with the madness, where family members step back emotionally from the chaos that so often accompanies drug abuse. It’s a way to reduce an addict’s power to hurt and manipulate those closest to them.

While each mother is at different stages of the process, ‘Joyce’ from Bacchus Marsh appears, on face value, the closest to a grim end.

For seven years her son has been so addicted to “anything he can get his hands on”, death appears the only choice left.

“I’m at the end of my journey of staying with him … if he dies, he dies, I can’t stop it. You just want it to end,” she says. “You think they will be better off, if he’s in such a bad place. I don’t have any magic answers … maybe I’m looking for a miracle, and there isn’t one.

“I don’t know if you come to terms with it at all. I just think that you get to the stage where at some point you have tried everything that you possibly can. Every single thing.”

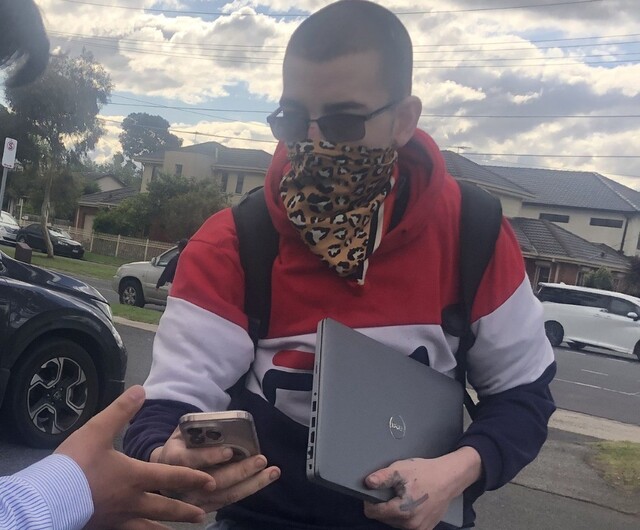

Every single thing includes filming her son while in the throes of one of many drug binges.

“I can’t believe I was like that,” her son had confessed through tears days later, as he watched himself convulse and eventually black out.

But the plan didn’t work. ‘James’ has overdosed so many times – at least four times in the family home over the past six months – that Joyce has become numb to it all.

“You have to face it [their possible death], if you like it or not. You have to face that they could die,” says mother of five ‘Sarah’ from Melton, who attends not because of her children, but her husband.

While she’s physically detached from him – he’s in Tasmania right now “trying to get off” – she’s yet to cut the emotional ties. His taste for drugs began with speed before it developed into a full-on ice addiction. Then came the “cycle of violence”, the paranoia, the psychosis and eventually the intervention order.

“There have been times I wished he was dead, how terrible is that? I love my husband with everything I have, but to get to that point, that’s the devastation of drugs. It’s like we’re addictees. They’re addicts, we’re addictees.”

Luckily, the group has allowed ‘Sarah’ to put more time into herself. “I feel like I’m loving myself more these days,” she says. “We still hope for our future, but how long do I wait?”

For ‘Donna’ of Bacchus Marsh, mother of two ice addicts aged 17 and 19, the waiting game takes place on a weekly basis.

“By the end of every weekend you wonder, Are they still going to be alive? Every weekend I know they’re doing all these things to themselves. I didn’t see either of them on Mother’s Day, which was a good thing.

“Every weekend, [I think] is it going to be this weekend? Are they still going to be here on Monday? I don’t know if I’m happy, sad, anything. I just want it to be over, really. I’m just tired of the merry-go-round. And I can’t get myself off.”

‘Sandra’, mother of a 23-year-old ice addict, is exhausted. Tired of the emotional extremes and the knowledge that even when she does find rare moments of calm, it’s merely a prelude to the inevitable “explosion”.

“They would climb Mt Everest to get it [ice],” the Myrniong resident says. “The addiction is so great.”

The “chaos business” as she calls it, has been so encompassing, she can’t recall why she kicked her son out of home in the first place.

“[He’s been on drugs] for years, I don’t know how long, probably for six years I’m guessing,” she says. “We slept for a week and a half in the passage way to keep him in his room; it was horrendous. He doesn’t live with us now. We had an intervention order because he was going to burn the house down at one stage. He was supposed to come on Mother’s Day for lunch. He worked with my husband on Friday … haven’t seen him since.”

It’s only as the conversation begins to flow over coffee, laughter and an endless supply of mints (if these women have a vice of their own, it’s definitely sugar) that Sandra suddenly remembers why he had to leave: he threatened to stab his sister. No wonder her thoughts often stray into some very dark places.

“I thought of death, I thought it would be good one time because you’d be at peace, and that’s sad, isn’t it?

“At one stage I thought, I don’t like him any more. I thought that’s a bit cruel, a mother who doesn’t like their own child. They just grind you down that much. It sounds selfish, but then you’ve got peace, it becomes so consuming.”

While there’s still a long road ahead for each of these women, they’re walking it more strongly than ever before, thanks to the group.

“We’re all detaching,” Joyce announces proudly. “We do care, but we’re able to keep a distance.”

For Sarah, having the group’s support has changed her life.

“It helps us be set free, to hold our heads up and get some purpose back into our lives and some direction. Who would have thought we’d need a journey to recovery?”

To contact the group, phone Jim Ross on 5366 4500.