“It’s funny how when someone dies, things they treasured turn out to be just that … things,” my father observes.

Four months after the death of his wife, my mother, we have started the job of clearing the house.

We started in the kitchen, among the hardware, believing pots would be less painful than coats, scarves, shoes and lace-edged handkerchiefs. Stupid really because, more than any other room, this was her domain. Yet, there was an element of necessity about tackling the pantry.

In the five and a half years between the stroke that prevented her coming home and her death, the pantry was much as she left it: provisioned to whip up a batch of biscuits, cake, tray of slice or pie at any moment.

It seemed like too much of an invasion of her turf, too much of an admission of defeat, to toss ingredients from which she conjured Anzacs, chocolate-chip cookies, ginger cake, apple pie and apricot bread.

But now it wasn’t the stale ingredients and out-of-date packages that worried me as much as the … things.

Unless you know their stories, how would you know the chipped tea cup she left in the flour bin as a measure belonged to her mother? Or that in the cutlery drawer the rusted ancient Foster’s bottle opener belonged to her father, and the vicious-looking ancient bone-handled carving fork to her grandparents.

Perhaps this is where people start to become hoarders; when the line between things and memories becomes blurred and objects take on a life of their own.

In my own kitchen there is one cheap white plate with a thin silver band worn to almost nothing by constant washing. The plate is unremarkable, but I know its secret; how it actually belongs to a mime and a clown named Anthony Verity who lives in an orange straw-bale house and works as a living statue known as Albert Stone.

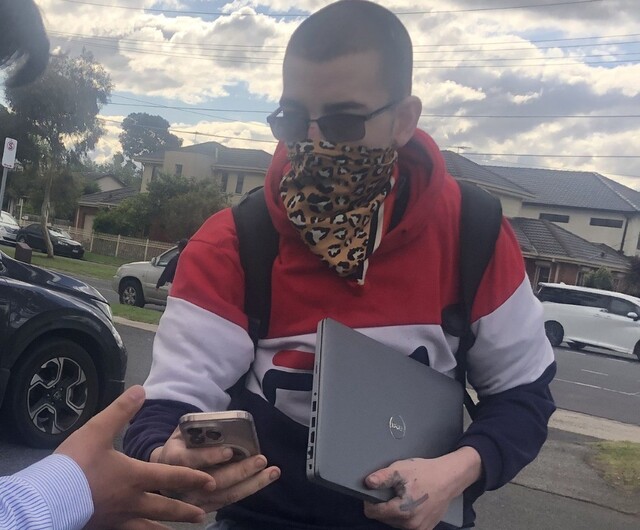

Many readers will have seen him dressed in a suit covered with rubber, grey paint and foam, with hands and face coated in grey make-up as he works the streets of Melbourne with gentle humour, chipping away at even the hardest of hearts.

The plate, crowned by chocolate cake fresh from Anthony’s informal coffee shop of a kitchen, returned to the office with a photographer one day by way of thanks for a story.

After the cake was demolished, I fully intended to return it. Washed and dried, it rattled around in the car boot for a while but I never seemed to be in the owner’s neighbourhood.

Eventually the orphaned plate insinuated itself among my crockery and, being a very handy three-quarter size, soon found itself adopted. That was eight years ago.

To me it’s a magic pudding of a plate, never entirely empty because it resonates with the story of a character made of stone.

It shares something of Albert’s inscrutable stillness amid the frantic city bustle and the beyond-words-feeling of connection with another time and place.

One – hopefully far distant – day the duty will befall others to look after my estate and no doubt the plate will be trashed as mismatched junk.

Things are not always what they seem.